Overview

Texas Pacific Land trust

(TPL from now) is one of the largest landowners in Texas. The Trust dates to

1888 and formed part of the land holdings of the old Texas & Pacific

Railroad; TPL is now the second-oldest “stock” on NYSE.

TPL operates the business

in two segments: Land and Resource Management and Water Services and Operations.

*Land

and Resource Management

This

segment encompasses the business of managing approximately 900,000 acres. The

revenue streams of this segment principally consist of royalties from oil and

gas, revenues from easements and commercial leases, and land and material

sales.

Revenues

is derived from the oil and gas royalty interests. Thus, in addition to being

subject to fluctuations in response to the market prices for oil and gas, the

oil and gas royalty revenues are also subject to decisions made by the owners

and operators of the oil and gas wells to which the royalty interest relate as

to investments in and production from those wells.

TPL

owns “non-participating perpetual royalty interests” (NPRIs) in about 456,000 acres.

NPRIs entitle TPL to a perpetual right to receive a fixed cost-free percentage

of production revenue. TPL also charges users for easements – for pipelines,

work crews, roadway rights, power lines, storage facilities, etc. Since its

land covers such a large area, almost any infrastructure project will cross TPL

land.

*Water

Services and Operations

TPL also controls the

water rights to these acres. As drilling is water intensive, this creates an

opportunity for TPL to charge for access to its aquifers and for water

recycling.

Horizon Kinetics, an investment adviser highly oriented in value investment

philosophy, owns a quarter of the shares and is involved in a case against the

trustees to convert TPL to a C corp. and improve disclosures and governance.

Although this conversion takes several months, it seems to be going well.

The Advantages

TPL´s land lies in the

western portion of the Permian Basin, known as the Delaware Trend. The Dept. of Energy not

too long ago determined that the Delaware Trend contains the world´s largest

oil and gas deposit outside of Saudi Arabia.

Until very recently, the

capital spending plans of drillers like Chevron, Exxon, EOG, Shell and Occidental

confirmed that they were planning to expand production for many years in the

Permian Basin.

We must also bear in mind

that US produces approximately 12-14% of global oil supply, and the lowest cost

curve is in the Permian.

As I wrote before, the TPL

royalties are perpetual, so any US energy collapse and oil price surge, would

drive production right back to these acres at materially higher prices.

It is relevant that TPL

has zero debt in its balance and that operating lease are not significant, we

must keep in mind that debt in good times are good for equity investors, but

very ugly in bad times.

Recent Events

All things about oil were

in shape until the recent war between Russia and Saudi Arabi comes on the

scene. The deal, that these two countries had, were broken, plunging oil wti

prices to around $20 (lowest level in 18 years). TPL has 19 years of production

that breaks even bellow $40, so $20 represented a must to close for most shale

oil companies in the Permian Base. This extreme situation forced to USA

intervene trying to find a truce that seems going well and oil prices are being

recovered.

A Short Story

TPL is highly profitable (ROC

+200%) and, with zero debt, the company has a great advantage in the recession

that we face.

Since 2010, TPL has passed

from $20 m up to $490 m in revenues, growing at 43% CAGR, and its EBIT has

multiplied by more than 20.

In the next picture we can observe in bars

revenues and EBIT in last 10 years, and how well correlated are with “Texas Oil

Production (mb/day)”

The secret to its success

is not hard to find: the company has no competition as the land (at the heart

of Permian Base) is theirs, period.

The

chart above reflects something not so obvious: TPL is not so strong correlated

with oil prices as we would expect at least in the long run. Therefore, one could

suspect that value creation occurring at TPL does not depend so much on oil

prices except some probable short-term noise which I don´t deny that there can

be.

Analyzing the Texas

Oil Production Data

The aim of this post is to

value the company according cash flows the company could generate in the

future.

I will employ a two-stage

valuation model, where we project revenues for the next five years and then

lower the growth rate to the Treasury bond rate of 0.61%

after that.

The reason to choose a

first stage of five years is that our power to predict revenues is limited by

our historical data.

Before we try to project

revenues for the next 5 years, I will analyze the time series data (of Texas

Oil Production) through 2014, using those data to forecast the Oil Production

through 2019 that we would have expected if there had been no unusual event,

and then compare the predicted Oil Production with the actual 2014-2019 data.

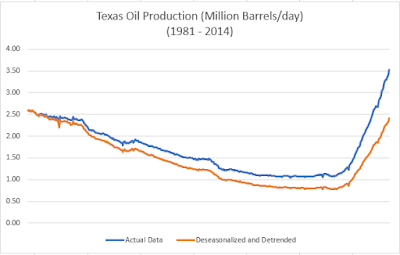

The first step in time

series analysis should always be to view the data:

Our first step is to

construct a table for average seasonal and trend factors to account seasonality

and trend from our data. Then we need to remove both seasonality and trend for

the pre-2014 time period, the result is shown following:

With our Deseasonalized

and detrended data, and armed with a software for statistical tools (Crystal

Ball, ModelRisk, etc), it is possible to fit a time series model to remaining

variability in the time series and forecast the post-2014 oil production. The

best Time Series Model I found was a variation of a “Geometric Brownian Motion

(GBM) model”, sometimes referred to as “random walk model”.

How good is our time series

model is measured with the Thiel´s U, a statistic that can provide such a

measure. The closer Thiel´s U is to zero, the better the forecast is.

To implement Thiel´s U in our oil production model, I calculate it simulating in the software of statistical tools. My results are the following:

Figure above shows a mean

Thiel´s U of 0.10 which I consider as a moderately good measure.

And now, we are ready to

forecast the next 5 years bellow:

The trend chart, suggest

that de median oil production is expected to be the same over the next 5 years.

One year into the future, the range of production is fairly narrow, but the

time a year passes, the forecast range extends from 2 mb/day to over an extreme

14 mb/day.

I will assume average value of distributions of oil production for each year as my base case:

Projection

of revenues for the next five years

In order to project

revenues into the future, I need to regress past revenues against a variable

that best fit my regression. Some candidates could be “WTI oil prices ($/barrel)”,

“gas oil prices” or “Texas oil production (mb/day)”, or a combination of these

variables.

I have tried several

combinations, but the best one is to focus on “Texas oil production”. Now you,

reader, can understand my effort in point 5 of this post.

If I run a regression

revenues against oil production (according our limited data from last 10 years),

we have an R-square high (75%) and an oil production coefficient highly

statistically significant (P-value = 0.001).

If I wish to forecast the

revenues that would result from whatever amount of oil production, we could use

the estimated relationship

Revenues ($ m) = -144.32 +

83.52 x Oil Production (mb/day)

But because of the limited

amount of data and because of chance, there is uncertainty about the true

relationship between oil production and revenues, and to simulate the

uncertainty in the relationship correctly, we need to adopt a different

procedure.

The method I will use is a

parametric Bootstrap. This procedure outputs bootstrap samples which are

constructed by simulating the sales level for each Oil Production level in the

original data set.

Finally, with my Bootstrap

model, I get Revenues for the next five years which are normal distributed as

follows:

In the figure above we observe

that the further we move away from the present, the wider our distributions and

less accurate our predictions, of course.

Final

Valuation

Now, we are ready to value

our company. In the next table I try to summarize my valuation

I was tempted to give some

probability to fail due to the next recession we face, but my probability is

zero because TPL has no competitor right now. My equity value is $2.439 billion,

there are 7.76 million shares outstanding, and my final valuation is $353.02 per

share.

The great deal of

uncertainty in this valuation are revenues for the next five years which are

driven by the oil production, but I can still estimate value in spite of that

uncertainty. In fact, that is what I have done in the simulation below:

In terms of base numbers,

the simulation does not change my view of TPL. My median value is $289.69, with

the tenth percentile at close to $147.81 and the ninetieth percentile at $576.11,

making it over valued, if it is priced at $457.00. The long tail on positive

end of the distribution implies that I would buy TPL with a smaller margin of

safety, because of the potential of significant upside.